It goes without saying that the architectural community has seldom considered polymeric cladding as a material of choice when specifying for traditional or historic neighborhood designs. But when the Vinyl Siding Institute (VSI) rolled out its newly published book, Architectural Design for Traditional Neighborhoods, the reception during its debut at the first two AIA-accredited industry events was quite positive.

During the AIA Louisiana Conference on “Modern Materials for Traditional Design” in New Orleans last September 12th and 13th, a broad spectrum of distributors, architects, developers and academics was introduced to this innovative work. Commissioned by the VSI but written by a renowned builder and several leading architects from the world of New Urbanism, Architectural Design for Traditional Neighborhoods demonstrates the tremendous advantages of using polymeric materials for designing traditional neighborhoods.

The reaction – according to Alex Fernandez, VSI’s Assistant Director – Advocacy & Government Affairs, was quite positive.

“It was surprising to see the strong response from the participants,” said Fernandez, “because they didn’t expect to see the revelations of what today’s modern materials are capable of, and were excited to hear that vinyl siding is one of the most sustainable products on the market.”

But as the new book maintains, the perception towards polymeric materials has changed, as evidenced by the successful applications of vinyl siding to buildings designed for “prestigious and discerning clients,” including Dartmouth College (page 11, Introduction).

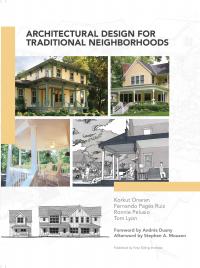

The book’s authors, Korkut Onaran, Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Ronnie Pelusio, and Tom Lyon, have leveraged decades of experience in designing and developing neighborhoods, as well as deep roots in the New Urbanism movement, to compile this opus for neighborhood design. The book emphasizes a “less is more” approach to achieving sustainable communities that are also quite beautiful. It moves away from over-adornment of individual facades and puts the focus on the entire block face as a design collective, giving way to natural elements that define the neighborhood – like a central square with diverse activities, and sidewalks lined with street trees that promote pedestrian lifestyles over dense traffic patterns. And it addresses the production realities of today’s home building industry by demonstrating how innovative materials – especially the growing offering of polymeric products – can be utilized to achieve both sustainability and traditional design objectives.

“It discusses what to require by code, and perhaps more importantly, what not to code,” Andres Duany (Founder of the Congress for the New Urbanism) argues in the book’s Foreward. “Costly materials will not overcome dismal suburban site plans.”

There are still those public landmark and historic designation stakeholders, as well as many architects who are dyed in the wool about not specifying polymeric materials for historic buildings and re-developments, or traditional neighborhoods for that matter.

“These hardcore architects are interested in learning about vinyl siding and polymeric cladding innovations, and are impressed with its benefits,” Fernandez asserts, “but they still won’t spec it. There is, however, a big enough portion of architects who are practical and are also committed to long-term sustainability. These are the ones that our members can develop relationships with, and the new book will be a powerful resource to help us educate them on achieving both long-term sustainability goals AND beautiful traditional designs with excellent durability and resiliency qualities. And from the moment Fernando (Pages Ruiz) opened the material array box, there were a lot of ‘oohs’ and ‘ahs’ from the attendees.”

To support his argument, Fernandez cites one participant - a prominent architect from downtown New Orleans - who actually turns down work from designated historic districts because she prefers to specify vinyl siding. The rules are so rigid about what materials to use, that she tells clients in that area that they should not hire her because the city won’t let her work with vinyl. Because she has no freedom as a designer, she feels that she could not justify taking their money because the work has already been carved out.

Fernandez added that the audience was very excited to see the vertical siding, as well as any samples presented with foam backing.

“People in the trade tend to be negative towards thinner materials, but traditional vinyl is very durable and extremely resource-efficient from a sustainability standpoint. Some polymeric cladding products are very rigid akin to a piece of wood – which is what the builders want.”

The book is strategically arranged in 4 chapters. The first chapter (Neighborhood Design) discusses planning active neighborhoods where people want to spend their daily lives, while Chapter 2 covers the rich inventory of Architectural Styles available in the U.S. Chapter 3 is all about Architectural Design, including the introduction of the concept of half stories along with helpful design guidelines for all the building elements – especially my favorite (and perhaps the most important to the New Urbanism movement) – front porches. And the final chapter (New Horizons in Building Materials) shows how innovative polymeric materials can play an integral role in the development of traditional neighborhoods while still enabling designers to stay true to the principals of authentic traditional neighborhood architecture.

Fernandez strongly believes that the way the book is organized, and the quality of the work really preaches to the growing choir of builders and architects.

“EVERYONE must read the introduction of the book! If you don’t know what we are trying to accomplish, read the intro. Any layperson can read it and walk away with a history of what the polymeric material industry has been doing to support good neighborhood design, as well as a strong understanding of all the possibilities vinyl siding offers that incorporate great design, sustainable solutions, and cost-effectiveness. VSI may have commissioned this book, but it’s driven by subject matter experts and the results of 3rd party government studies on sustainability.”

At the second presentation, which was held at the prestigious DPZ CoDesign firm in Miami, Fernando Pages Ruiz emphasized how the versatility of polymeric products can be advantageous for changes in traditional construction patterns.

“Architecture is a pattern language, and like all languages, it changes and evolves,” asserts Pages Ruiz. “The American way is to be flexible. In this spirit, polymeric materials do a good job of replacing traditional materials. They may not be identical, but they sure are beautiful.”

Fernando Pages Ruiz started his presentation by showing some eye-catching traditional designs, but intentionally did not volunteer the use of polymeric materials until after the crowd expressed its approval.

Fernando Pages Ruiz stated that “architects don’t spec vinyl because they’ve seen it before on bad designs. When they see it on beautiful designs, they don’t know they are looking at vinyl or think much about what the material is. My co-author (Korkut Onaran) was the historic planner for his neighborhood in Colorado and didn’t realize that beautiful reproduction patterns had polymeric materials. This is how he became a convert.”

Another approach Fernando Pages Ruiz used that was quite effective was asking and answering two simple questions about using modern materials for traditional neighborhoods:

- Do you have to use it? NO!

- Can you use it? YES, and here’s why you should.

First, he stressed the durability of vinyl in tough climates. Pages Ruiz mentioned that – a few years ago – he showed beautiful designs of local houses that used polymeric materials at the Congress for the New Urbanism conference in Buffalo, NY.

“Vinyl siding and related products are popular in snow belt communities because people are tired of scraping paint! It’s a trouble-free, extremely durable product that also has a great aesthetic.”

Second, other claddings are very limited in their product offerings. They will only have 6-inch and 8-inch product categories, so they don’t have the depth that vinyl has. And designers crave flexibility and more options.

Third, many traditional neighborhood redevelopment projects will require detailed ornamentation that is both difficult and expensive to maintain. There are great polymeric products useful in designing highly ornamental styles, such as Victorian and Italianate, which will provide the decorative details needed without the costly upkeep.

In summing up the results of the first two presentations, both Fernandez and Pages Ruiz felt very strongly that – while there is more work to be done – they made enormous progress thanks to the new book release.

“The architects were intrigued enough that they asked a lot of questions long after the conference was over, and one team was even considering using vinyl for a project in the northwest,” Pages Ruiz claims.

“Typically, if the architects aren’t interested, they go right back to work when it’s over without asking any questions. After our talk, not only did they ask a lot of questions, but I had to break out the material array box again to help answer the questions! Long after the presentation, I went back into the work studio to confer with a colleague about a project we are collaborating on, and I had to field 3-4 more questions from her colleagues, who stopped what they were working on as soon as they saw me enter the room!”